Story of How Mt Vesuvius Will Erupt Again to Reach the Woman in the Water

| Mount Vesuvius | |

|---|---|

Mount Vesuvius as seen from the ruins of Pompeii, which was destroyed in the eruption of Advert 79. The agile cone is the loftier peak on the left side; the smaller 1 on the correct is role of the Somma caldera wall. | |

| Highest bespeak | |

| Elevation | 1,281 chiliad (4,203 ft) |

| Prominence | ane,232 yard (4,042 ft) |

| Coordinates | twoscore°49′Northward 14°26′E / 40.817°N fourteen.433°East / 40.817; xiv.433 Coordinates: 40°49′N 14°26′Due east / 40.817°N fourteen.433°E / 40.817; 14.433 |

| Naming | |

| Native name |

|

| Geography | |

| Mountain Vesuvius Mount Vesuvius in Campania, Italy | |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 25,000 years before nowadays to 1944; historic period of volcano = c. 17,000 years to present |

| Mountain type | Somma-stratovolcano |

| Volcanic arc/chugalug | Campanian volcanic arc |

| Last eruption | 17–23 March 1944 |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Walk |

Mountain Vesuvius ( viss-OO-vee-əs; Italian: Vesuvio [i] [veˈzuːvjo, -ˈsuː-]; Neapolitan: 'O Vesuvio [2] [o vəˈsuːvjə], likewise 'A muntagna or 'A montagna ;[iii] Latin: Vesuvius [4] [wɛˈsʊwɪ.ʊs], also Vesevius , Vesvius or Vesbius [v]) is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, most ix km (5.6 mi) eastward of Naples and a curt distance from the shore. Information technology is one of several volcanoes which grade the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuvius consists of a large cone partially encircled past the steep rim of a summit caldera, caused by the collapse of an before and originally much higher structure.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 destroyed the Roman cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis and Stabiae, as well as several other settlements. The eruption ejected a deject of stones, ashes and volcanic gases to a pinnacle of 33 km (21 mi), erupting molten rock and pulverized pumice at the rate of 6×tenfive cubic metres (7.8×10five cu yd) per second.[vi] More than i,000 people are thought to accept died in the eruption, though the exact toll is unknown. The just surviving eyewitness account of the event consists of two letters by Pliny the Younger to the historian Tacitus.[vii]

Vesuvius has erupted many times since and is the just volcano on the European mainland to have erupted within the last hundred years. Today, it is regarded as one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world because of the population of 3,000,000 people living near enough to be affected past an eruption, with 600,000 in the danger zone, making it the most densely populated volcanic region in the world. It has a trend towards violently explosive eruptions, which are now known equally Plinian eruptions.[viii]

Mythology

Vesuvius has a long historic and literary tradition. Information technology was considered a divinity of the Genius type at the time of the eruption of Ad 79: information technology appears nether the inscribed proper noun Vesuvius equally a ophidian in the decorative frescos of many lararia , or household shrines, surviving from Pompeii. An inscription from Capua[ix] to IOVI VESVVIO indicates that he was worshipped as a power of Jupiter; that is, Jupiter Vesuvius.[10]

The Romans regarded Mount Vesuvius to be devoted to Hercules.[11] The historian Diodorus Siculus relates a tradition that Hercules, in the performance of his labors, passed through the land of nearby Cumae on his manner to Sicily and establish there a place called "the Phlegraean Plain" (Φλεγραῖον πεδίον, "plain of fire"), "from a hill which anciently vomited out fire ... at present called Vesuvius."[12] It was inhabited by bandits, "the sons of the Earth," who were giants. With the aid of the gods, he pacified the region and went on. The facts backside the tradition, if whatever, remain unknown, as does whether Herculaneum was named after information technology. An epigram by the poet Martial in 88 Advert suggests that both Venus, patroness of Pompeii, and Hercules were worshipped in the region devastated by the eruption of 79.[13]

Metropolis of Naples with Mount Vesuvius at sunset

Etymology

Vesuvius was a proper noun of the volcano in frequent use by the authors of the late Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. Its collateral forms were Vesaevus , Vesevus , Vesbius and Vesvius .[14] Writers in aboriginal Greek used Οὐεσούιον or Οὐεσούιος . Many scholars since so have offered an etymology. As peoples of varying ethnicity and language occupied Campania in the Roman Iron Age, the etymology depends to a large degree on the presumption of what language was spoken at that place at the fourth dimension. Naples was settled past Greeks, every bit the proper name Nea-polis , "New City", testifies. The Oscans, an Italic people, lived in the countryside. The Latins also competed for the occupation of Campania. Etruscan settlements were in the vicinity. Other peoples of unknown provenance are said to have been there at some fourth dimension past diverse ancient authors.

Some theories about its origin are:

- From Greek οὔ = "not" prefixed to a root from or related to the Greek word σβέννυμι = "I quench", in the sense of "unquenchable".[14] [xv]

- From Greek ἕω = "I hurl" and βίη "violence", "hurling violence", *vesbia, taking advantage of the collateral grade.[xvi]

- From an Indo-European root, *eus- < *ewes- < *(a)wes-, "polish" sense "the one who lightens", through Latin or Oscan.[17]

- From an Indo-European root *wes = "hearth" (compare e.k. Vesta)

Appearance

Vesuvius is a "humpbacked" peak, consisting of a large cone (Gran Cono) partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera caused past the collapse of an earlier (and originally much higher) structure called Mount Somma.[18] The Gran Cono was produced during the A.D. 79 eruption. For this reason, the volcano is also called Somma-Vesuvius or Somma-Vesuvio.[19]

The caldera started forming during an eruption effectually 17,000–18,000 years ago[twenty] [21] [22] and was enlarged by later paroxysmal eruptions,[23] ending in the one of Advertisement 79. This structure has given its name to the term "somma volcano", which describes any volcano with a summit caldera surrounding a newer cone.[24]

The height of the main cone has been constantly changed by eruptions but was ane,281 thousand (iv,203 ft) in 2010.[21] Monte Somma is i,132 m (3,714 ft) high, separated from the main cone past the valley of Atrio di Cavallo, which is 5 km (3.1 mi) long. The slopes of the volcano are scarred past lava flows, while the rest are heavily vegetated, with scrub and forests at college altitudes and vineyards lower downward. Vesuvius is still regarded as an active volcano, although its current activity produces little more than than sulfur-rich steam from vents at the lesser and walls of the crater. Vesuvius is a stratovolcano at a convergent boundary, where the African Plate is being subducted beneath the Eurasian Plate. Layers of lava, ash, scoria and pumice make upwardly the volcanic peak. Their mineralogy is variable, but mostly silica-undersaturated and rich in potassium, with phonolite produced in the more explosive eruptions[25] (e.g. the eruption in 1631 displaying a consummate stratigraphic and petrographic description: phonolite was firstly erupted, followed past a tephritic phonolite and finally a phonolitic tephrite).[26]

Formation

Vesuvius was formed as a issue of the collision of two tectonic plates, the African and the Eurasian. The former was subducted beneath the latter, deeper into the globe. As the h2o-saturated sediments of the oceanic African plate were pushed to hotter depths within the planet, the water boiled off and lowered the melting point of the upper mantle enough to partially cook the rocks. Because magma is less dense than the solid rock around it, information technology was pushed upward. Finding a weak spot at the Globe'due south surface, information technology broke through, thus forming the volcano.[ citation needed ]

The volcano is i of several which form the Campanian volcanic arc. Others include Campi Flegrei, a big caldera a few kilometers to the north due west, Mount Epomeo, xx kilometres (12 mi) to the west on the island of Ischia, and several undersea volcanoes to the south. The arc forms the southern stop of a larger chain of volcanoes produced by the subduction procedure described above, which extends northwest forth the length of Italy every bit far equally Monte Amiata in Southern Tuscany. Vesuvius is the only one to take erupted within recent history, although some of the others have erupted inside the last few hundred years. Many are either extinct or have not erupted for tens of thousands of years.

Eruptions

Mount Vesuvius has erupted many times. The eruption in Ad 79 was preceded by numerous others in prehistory, including at least three significantly larger ones, including the Avellino eruption effectually 1800 BC which engulfed several Statuary Age settlements. Since AD 79, the volcano has besides erupted repeatedly, in 172, 203, 222, perhaps in 303, 379, 472, 512, 536, 685, 787, around 860, around 900, 968, 991, 999, 1006, 1037, 1049, around 1073, 1139, 1150, and there may have been eruptions in 1270, 1347, and 1500.[23] The volcano erupted again in 1631, half dozen times in the 18th century (including 1779 and 1794), viii times in the 19th century (notably in 1872), and in 1906, 1929 and 1944. There take been no eruptions since 1944, and none of the eruptions afterwards Advertisement 79 were as big or destructive as the Pompeian i.

The eruptions vary profoundly in severity but are characterized past explosive outbursts of the kind dubbed Plinian afterwards Pliny the Younger, a Roman author who published a detailed clarification of the AD 79 eruption, including his uncle's death.[27] On occasion, eruptions from Vesuvius have been so large that the whole of southern Europe has been blanketed by ash; in 472 and 1631, Vesuvian ash barbarous on Constantinople (Istanbul), over 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) away. A few times since 1944, landslides in the crater have raised clouds of ash dust, raising false alarms of an eruption.

Since 1750, vii of the eruptions of Vesuvius have had durations of more 5 years, more than than whatever other volcano except Etna. The 2 nearly recent eruptions of Vesuvius (1875–1906 and 1913–1944) lasted more than 30 years each.[28]

Earlier AD 79

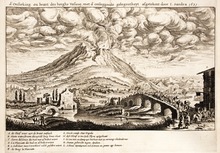

Vesuvius erupting. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection.

Scientific knowledge of the geologic history of Vesuvius comes from cadre samples taken from a two,000 m (half dozen,600 ft) plus bore hole on the flanks of the volcano, extending into Mesozoic rock. Cores were dated by potassium–argon and argon–argon dating.[29] The surface area has been subject to volcanic activity for at to the lowest degree 400,000 years; the everyman layer of eruption material from the Somma caldera lies on top of the 40,000-twelvemonth‑former Campanian ignimbrite produced by the Campi Flegrei complex.

- 25,000 years ago: Vesuvius started forming in the Codola Plinian eruption.[18]

- Vesuvius was then built upwardly past a series of lava flows, with some smaller explosive eruptions interspersed between them.

- Virtually 19,000 years agone: the fashion of eruption changed to a sequence of large explosive Plinian eruptions, of which the Advertizement 79 one was the most recent. The eruptions are named afterwards the tephra deposits produced by them, which in plough are named afterwards the place where the deposits were first identified:[xxx]

- 18,300 years ago: the Basal Pumice (Pomici di Base of operations) eruption, VEI 6, the original formation of the Somma caldera. The eruption was followed by a period of much less fierce, lava-producing eruptions.[22]

- sixteen,000 years agone: the Green Pumice (Pomici Verdoline) eruption, VEI 5.[18]

- Around xi,000 years ago: the Lagno Amendolare eruption, smaller than the Mercato eruption.

- viii,000 years agone: the Mercato eruption (Pomici di Mercato) – also known as Pomici Gemelle or Pomici Ottaviano, VEI 6.[eighteen]

- Around 5,000 years ago: ii explosive eruptions smaller than the Avellino eruption.

- 3,800 years ago: the Avellino eruption (Pomici di Avellino), VEI six; its vent was obviously two km (1.two mi) west of the current crater and the eruption destroyed several Bronze Age settlements of the Apennine culture. Several carbon dates on woods and bones offer a range of possible dates of nigh 500 years in the mid-2d millennium BC. In May 2001, almost Nola, Italian archaeologists using the technique of filling every cavity with plaster or substitute compound recovered some remarkably well-preserved forms of perishable objects, such as contend rails, a bucket and especially in the vicinity thousands of homo footprints pointing into the Apennines to the northward. The settlement had huts, pots and goats. The residents had hastily abandoned the hamlet, leaving it to be buried under pumice and ash in much the aforementioned way that Pompeii and Herculaneum were later preserved.[31] [32] Pyroclastic surge deposits were distributed to the northwest of the vent, travelling every bit far as xv km (nine.3 mi) from it, and lie up to three g (9.8 ft) deep in the area now occupied by Naples.[33]

- The volcano then entered a phase of more frequent, but less fierce eruptions, until the most recent Plinian eruption, which destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum.

- The concluding of these may have been in 217 BC.[23] In that location were earthquakes in Italy during that year and the sun was reported equally being dimmed by gray brume or dry fog. Plutarch wrote of the sky beingness on fire near Naples, and Silius Italicus mentioned in his epic verse form Punica [34] [35] that Vesuvius had thundered and produced flames worthy of Mount Etna in that year, although both authors were writing around 250 years after. Greenland ice core samples of around that period show relatively high acidity, which is causeless to have been caused by atmospheric hydrogen sulfide.[36]

- The volcano was then quiet (for 295 years, if the 217 BC date for the last previous eruption is true) and was described by Roman writers every bit having been covered with gardens and vineyards, except at the peak, which was craggy. The volcano may have had just one summit at that time, judging by a wall painting, "Bacchus and Vesuvius", establish in a Pompeian house, the Firm of the Centenary (Casa del Centenario).

Several surviving works written over the 200 years preceding the Advert 79 eruption describe the mount as having had a volcanic nature, although Pliny the Elder did not depict the mountain in this way in his Naturalis Historia:[37]

- The Greek historian Strabo (c. 63 BC – Advertizement 24) described the mountain in Book V, Chapter iv of his Geographica [38] as having a predominantly flat, barren summit covered with sooty, ash-coloured rocks and suggested that it might once accept had "craters of fire". He too perceptively suggested that the fertility of the surrounding slopes may be due to volcanic action, every bit at Mount Etna.

- In Book II of De architectura,[39] the architect Vitruvius (c. 80–70 BC –?) reported that fires had in one case existed abundantly below the peak and that it had spouted fire onto the surrounding fields. He went on to describe Pompeiian pumice every bit having been burnt from some other species of stone.

- Diodorus Siculus (c. 90 BC – c. 30 BC), another Greek writer, wrote in Book 4 of his Bibliotheca Historica that the Campanian evidently was called fiery (Phlegrean) because of the summit, Vesuvius, which had spouted flames like Etna and showed signs of the burn that had burnt in ancient history.[forty]

Eruption of AD 79

In Advert 79, Vesuvius erupted in one of the most catastrophic eruptions of all fourth dimension. Historians have learned nigh the eruption from the eyewitness account of Pliny the Younger, a Roman ambassador and poet.[41] In the surviving copies of the letters, several dates are given.[42] The latest prove supports earlier findings and indicates that the eruption occurred after 17 October.[43]

The volcano ejected a cloud of stones, ashes and volcanic gases to a top of 33 km (21 mi), spewing molten rock and pulverized pumice at the rate of half-dozen×x5 cubic metres (vii.viii×105 cu yd) per second, ultimately releasing 100,000 times the thermal energy released by the Hiroshima-Nagasaki bombings.[44] The cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum were destroyed by pyroclastic surges and the ruins buried under tens of metres of tephra.[44] [41]

Precursors and foreshocks

The AD 79 eruption was preceded by a powerful convulsion in 62, which acquired widespread devastation around the Bay of Naples, and peculiarly to Pompeii.[45] Some of the damage had notwithstanding not been repaired when the volcano erupted.[46] The deaths of 600 sheep from "tainted air" in the vicinity of Pompeii indicates that the earthquake of Advertizing 62 may have been related to new action by Vesuvius.[47]

The Romans grew accepted to minor earth tremors in the region; the author Pliny the Younger even wrote that they "were not peculiarly alarming because they are frequent in Campania". Small earthquakes started taking place four days earlier the eruption[46] becoming more than frequent over the next four days, but the warnings were not recognized.[a]

Scientific analysis

Pompeii and Herculaneum, likewise as other cities affected by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The black cloud represents the general distribution of ash, pumice and cinders. Modern coast lines are shown.

Reconstructions of the eruption and its effects vary considerably in the details but accept the aforementioned overall features. The eruption lasted ii days. The morning time of the first day was perceived as normal by the only bystander to leave a surviving certificate, Pliny the Younger. In the middle of the day, an explosion threw upwards a high-altitude column from which ash and pumice began to fall, blanketing the area. Rescues and escapes occurred during this fourth dimension. At some time in the night or early on the adjacent day, pyroclastic surges in the close vicinity of the volcano began. Lights were seen on the superlative interpreted every bit fires. People every bit far away every bit Misenum fled for their lives. The flows were rapid-moving, dumbo and very hot, knocking down wholly or partly all structures in their path, incinerating or suffocating all population remaining there and altering the landscape, including the coastline. These were accompanied by additional lite tremors and a mild tsunami in the Bay of Naples. By late afternoon of the 2d solar day, the eruption was over, leaving only haze in the temper through which the sun shone weakly.

The latest scientific studies of the ash produced past Vesuvius reveal a multi-phase eruption.[48] The initial major explosion produced a cavalcade of ash and pumice ranging betwixt 15 and 30 kilometres (49,000 and 98,000 ft) high, which rained on Pompeii to the southeast but non on Herculaneum upwind. The chief energy supporting the column came from the escape of steam superheated past the magma, created from seawater seeping over time into the deep faults of the region, that came into interaction with magma and estrus.

Afterward, the cloud complanate as the gases expanded and lost their capability to support their solid contents, releasing it equally a pyroclastic surge, which offset reached Herculaneum merely not Pompeii. Additional blasts reinstituted the cavalcade. The eruption alternated between Plinian and Peléan six times. Surges 3 and four are believed by the authors to take buried Pompeii.[49] Surges are identified in the deposits by dune and cross-bedding formations, which are non produced past fallout.

Some other study used the magnetic characteristics of over 200 samples of roof-tile and plaster fragments collected around Pompeii to estimate equilibrium temperature of the pyroclastic menstruation.[50] The magnetic report revealed that on the first day of the eruption a fall of white pumice containing clastic fragments of up to 3 centimetres (1.2 in) fell for several hours.[51] It heated the roof tiles upwards to 140 °C (284 °F).[52] This menstruum would accept been the last opportunity to escape.

The plummet of the Plinian columns on the second day caused pyroclastic density currents (PDCs) that devastated Herculaneum and Pompeii. The depositional temperature of these pyroclastic surges ranged up to 300 °C (572 °F).[53] Any population remaining in structural refuges could not accept escaped, equally the city was surrounded by gases of incinerating temperatures. The lowest temperatures were in rooms under collapsed roofs. These were as low as 100 °C (212 °F).[54]

The two Plinys

The only surviving eyewitness business relationship of the event consists of two letters by Pliny the Younger to the historian Tacitus.[7] Pliny the Younger describes, amongst other things, the final days in the life of his uncle, Pliny the Elder. Observing the first volcanic activeness from Misenum across the Bay of Naples from the volcano, approximately 35 kilometres (22 mi), the elderberry Pliny launched a rescue fleet and went himself to the rescue of a personal friend. His nephew declined to join the party. I of the nephew's letters relates what he could discover from witnesses of his uncle's experiences.[55] [56] In a second letter of the alphabet, the younger Pliny details his ain observations after the divergence of his uncle.[57] [58]

The two men saw an extraordinarily dense cloud rising rapidly above the peak. This cloud and a asking past a messenger for an evacuation by ocean prompted the elder Pliny to order rescue operations in which he sailed abroad to participate. His nephew attempted to resume a normal life, just that night a tremor awoke him and his mother, prompting them to abandon the house for the courtyard. Further tremors about dawn caused the population to carelessness the village and caused disastrous wave action in the Bay of Naples.

The early on light was obscured by a blackness deject through which shone flashes, which Pliny likens to canvass lightning, but more extensive. The cloud obscured Signal Misenum most at manus and the island of Capraia (Capri) across the bay. Fearing for their lives, the population began to call to each other and movement back from the declension along the road. A rain of ash barbarous, causing Pliny to shake it off periodically to avoid beingness buried. Later that aforementioned mean solar day the pumice and ash stopped falling and the sun shone weakly through the deject, encouraging Pliny and his mother to return to their home and look for news of Pliny the Elder.

Pliny's uncle, Pliny the Elderberry, was in command of the Roman armada at Misenum and had meanwhile decided to investigate the phenomenon at shut hand in a light vessel. As the ship was preparing to get out the surface area, a messenger came from his friend Rectina (married woman of Tascius[59]) living on the coast near the foot of the volcano, explaining that her party could only get away by sea and asking for rescue. Pliny ordered the firsthand launching of the fleet galleys to the evacuation of the declension. He connected in his light ship to the rescue of Rectina's party.

He prepare off across the bay simply in the shallows on the other side encountered thick showers of hot cinders, lumps of pumice and pieces of rock. Advised by the helmsman to plough back, he stated "Fortune favors the brave" and ordered him to go on on to Stabiae (about 4.5 kilometers from Pompeii).

Pliny the Elder and his party saw flames coming from several parts of the crater. After staying overnight, the party was driven from the edifice past an accumulation of cloth, presumably tephra, which threatened to block all egress. They woke Pliny, who had been napping and emitting loud snoring. They elected to have to the fields with pillows tied to their heads to protect them from the raining droppings. They approached the beach again only the wind prevented the ships from leaving. Pliny sat downwardly on a sail that had been spread for him and could non rise fifty-fifty with assistance when his friends departed. Though Pliny the Elder died, his friends ultimately escaped past state.[60]

In the first letter to Tacitus, Pliny the Younger suggested that his uncle's expiry was due to the reaction of his weak lungs to a cloud of poisonous, sulphurous gas that wafted over the group. Still, Stabiae was 16 km from the vent (roughly where the modern boondocks of Castellammare di Stabia is situated) and his companions were apparently unaffected by the volcanic gases, and so information technology is more likely that the corpulent Pliny died from some other cause, such as a stroke or heart attack.[61] His body was found with no apparent injuries on the next day, subsequently dispersal of the plume.

Casualties

Pompeii, with Vesuvius towering above

Along with Pliny the Elder, the only other noble casualties of the eruption to be known by name were Agrippa (a son of the Herodian Jewish princess Drusilla and the procurator Antonius Felix) and his wife.[62]

By 2003, around 1,044 casts made from impressions of bodies in the ash deposits had been recovered in and around Pompeii, with the scattered bones of another 100.[63] The remains of nigh 332 bodies have been constitute at Herculaneum (300 in arched vaults discovered in 1980).[64] What per centum these numbers are of the total dead or the percentage of the dead to the total number at risk remain unknown.

Thirty-eight per centum of the 1,044 were found in the ash autumn deposits, the majority within buildings. These are idea to have been killed mainly by roof collapses, with the smaller number of victims found exterior of buildings probably beingness killed by falling roof slates or by larger rocks thrown out by the volcano. The remaining 62% of remains found at Pompeii were in the pyroclastic surge deposits,[63] and thus were probably killed by them – probably from a combination of suffocation through ash inhalation and blast and debris thrown around. Examination of cloth, frescoes and skeletons shows that, in contrast to the victims found at Herculaneum, it is unlikely that high temperatures were a significant cause of the destruction at Pompeii. Herculaneum, which was much closer to the crater, was saved from tephra falls past the current of air management, but was buried under 23 metres (75 ft) of material deposited by pyroclastic surges. It is likely that near, or all, of the known victims in this town were killed by the surges.

People defenseless on the former seashore by the kickoff surge died of thermal shock. The rest were full-bodied in arched chambers at a density of equally high as 3 persons per square metre. Every bit just 85 metres (279 ft) of the declension have been excavated, further casualties may be discovered.

Afterward eruptions from the 3rd to the 19th centuries

Since the eruption of AD 79, Vesuvius has erupted around 3 dozen times.

- It erupted over again in 203, during the lifetime of the historian Cassius Dio.

- In 472, it ejected such a volume of ash that ashfalls were reported as far away as Constantinople (760 mi.; one,220 km).

- The eruptions of 512 were and then severe that those inhabiting the slopes of Vesuvius were granted exemption from taxes by Theodoric the Great, the Gothic king of Italian republic.

- Farther eruptions were recorded in 787, 968, 991, 999, 1007 and 1036 with the first recorded lava flows.

The volcano became quiescent at the end of the 13th century, and in the following years it again became covered with gardens and vineyards equally of old. Even the within of the crater was moderately filled with shrubbery.

- Vesuvius entered a new phase in December 1631, when a major eruption cached many villages under lava flows, killing around three,000 people. Torrents of lahar were as well created, adding to the devastation. Activeness thereafter became almost continuous, with relatively astringent eruptions occurring in 1660, 1682, 1694, 1698, 1707, 1737, 1760, 1767, 1779, 1794, 1822, 1834, 1839, 1850, 1855, 1861, 1868, 1872, 1906, 1926, 1929, and 1944.

Eruptions in the 20th century

- The eruption of 5 April 1906[65] [66] killed more than 100 people and ejected the nigh lava ever recorded from a Vesuvian eruption. Italian authorities were preparing to hold the 1908 Summer Olympics when Mountain Vesuvius violently erupted, devastating the metropolis of Naples and surrounding comunes. Funds were diverted to reconstructing Naples, and a new site for the Olympics had to be found.

- Vesuvius was active from 1913 through 1944, with lava filling the crater and occasional outflows of small amounts of lava.[67]

- That eruptive menses ended in the major eruption of March 1944, which destroyed the villages of San Sebastiano al Vesuvio, Massa di Somma, and Ottaviano, and role of San Giorgio a Cremano.[68] From xiii to xviii March 1944, activity was confined within the rim. Finally, on 18 March 1944, lava overflowed the rim. Lava flows destroyed nearby villages from 19 March through 22 March.[69] On 24 March, an explosive eruption created an ash plume and a small pyroclastic flow.

In March 1944, the United States Ground forces Air Forces (USAAF) 340th Bombardment Group was based at Pompeii Airfield about Terzigno, Italian republic, just a few kilometres from the eastern base of the volcano. The tephra and hot ash from multiple days of the eruption damaged the fabric control surfaces, the engines, the Plexiglas windscreens and the gun turrets of the 340th's B-25 Mitchell medium bombers. Estimates ranged from 78 to 88 aircraft destroyed.[70]

Ash is swept off the wings of an American B-25 Mitchell medium bomber of the 340th Bombardment Group on 23 March 1944 subsequently the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

The eruption could be seen from Naples. Different perspectives and the damage caused to the local villages were recorded by USAAF photographers and other personnel based nearer to the volcano.[71]

Hereafter

Large Vesuvian eruptions which emit volcanic material in quantities of about 1 cubic kilometre (0.24 cu mi), the most recent of which overwhelmed Pompeii and Herculaneum, accept happened after periods of inactivity of a few thousand years. Sub-Plinian eruptions producing about 0.one cubic kilometres (0.024 cu mi), such as those of 472 and 1631, take been more than frequent with a few hundred years betwixt them. From the 1631 eruption until 1944, there was a comparatively small eruption every few years, emitting 0.001–0.01 km³ of magma. It seems that for Vesuvius, the amount of magma expelled in an eruption increases very roughly linearly with the interval since the previous one, and at a rate of around 0.001 cubic kilometres (0.00024 cu mi) for each twelvemonth.[72] This gives an approximate figure of 0.075 cubic kilometres (0.018 cu mi) for an eruption after 75 years of inactivity.

Magma sitting in an underground chamber for many years will get-go to see higher melting point constituents such as olivine crystallizing out. The effect is to increase the concentration of dissolved gases (more often than not sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide) in the remaining liquid magma, making the subsequent eruption more violent. As gas-rich magma approaches the surface during an eruption, the huge drop in internal force per unit area caused by the reduction in weight of the overlying rock (which drops to zero at the surface) causes the gases to come out of solution, the volume of gas increasing explosively from nothing to mayhap many times that of the accompanying magma. Additionally, the removal of the higher melting point material will raise the concentration of felsic components such as silicates potentially making the magma more viscous, adding to the explosive nature of the eruption.

The surface area around the volcano is now densely populated.

The government emergency plan for an eruption therefore assumes that the worst case will exist an eruption of similar size and blazon to the 1631 VEI iv[73] eruption. In this scenario, the slopes of the volcano, extending out to well-nigh 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) from the vent, may exist exposed to pyroclastic surges sweeping down them, whilst much of the surrounding area could suffer from tephra falls. Considering of prevailing winds, towns and cities to the south and east of the volcano are most at risk from this, and it is assumed that tephra accumulation exceeding 100 kilograms per square metre (twenty lb/sq ft)—at which point people are at risk from collapsing roofs—may extend out as far every bit Avellino to the east or Salerno to the southward-east. Towards Naples, to the north west, this tephra fall adventure is assumed to extend barely past the slopes of the volcano.[72] The specific areas actually affected past the ash cloud depend upon the detail circumstances surrounding the eruption.

The plan assumes betwixt two weeks' and 20 days' observe of an eruption and foresees the emergency evacuation of 600,000 people, nigh entirely comprising all those living in the zona rossa ("red zone"), i.e. at greatest adventure from pyroclastic flows.[viii] [74] The evacuation, past train, ferry, car, and bus, is planned to take about seven days, and the evacuees would mostly be sent to other parts of the country, rather than to safe areas in the local Campania region, and may accept to stay away for several months. Notwithstanding, the dilemma that would face up those implementing the plan is when to starting time this massive evacuation: If it starts also late, thousands could be killed, whereas if information technology is started too early, the indicators of an eruption may turn out to be a simulated alarm. In 1984, 40,000 people were evacuated from the Campi Flegrei area, another volcanic complex near Naples, but no eruption occurred.[74]

The crater of Vesuvius in 2012

Ongoing efforts are being made by the government at various levels (especially of Campania) to reduce the population living in the cerise zone, by demolishing illegally synthetic buildings, establishing a national park around the whole volcano to prevent the future construction of buildings[74] and by offer sufficient financial incentives to people for moving away.[75] One of the underlying goals is to reduce the time needed to evacuate the expanse, over the side by side 20 to thirty years, to two or three days.[76]

The volcano is closely monitored by the Osservatorio Vesuvio in Naples with all-encompassing networks of seismic and gravimetric stations, a combination of a GPS-based geodetic array and satellite-based synthetic aperture radar to measure ground movement and by local surveys and chemical analyses of gases emitted from fumaroles. All of this is intended to track magma rise underneath the volcano. No magma has been detected within 10 km of the surface, and so the volcano is classified by the Observatory equally at a Basic or Green Level.[77]

National park

The area effectually Vesuvius was officially declared a national park on 5 June 1995.[78] The tiptop of Vesuvius is open to visitors, and in that location is a pocket-sized network of paths around the volcano that are maintained by the park authorities on weekends. There is access by road to inside 200 metres (660 ft) of the height (measured vertically), only thereafter access is on human foot just. In that location is a spiral walkway around the volcano from the road to the crater.

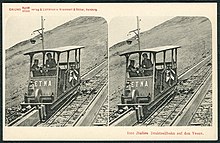

"Funiculì, Funiculà"

The get-go funicular cablevision machine on Mount Vesuvius opened in 1880. It was later destroyed by the March 1944 eruption. "Funiculì, Funiculà", a Neapolitan language song with lyrics by journalist Peppino Turco ready to music past composer Luigi Denza, commemorates its opening.[79]

Encounter also

- Battle of Mountain Vesuvius

- List of volcanic eruptions by death toll

- List of volcanoes in Italian republic

- Listing of stratovolcanoes

- Volcanic explosivity index

Notes

- ^ The dates of the earthquakes and of the eruption are contingent on a final decision of the fourth dimension of year, but in that location is no reason to modify the relative sequence.

References

- ^ "Vesuvio nell'Enciclopedia Treccani". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved vii February 2021.

- ^ "Neapolitan/manufactures – Wikibooks, open books for an open earth". en.wikibooks.org . Retrieved 7 Feb 2021.

- ^ Alfonso Grasso, ed. (2007). "Il Vesuvio" [Vesuvius]. ilportaledelsud.org (in Italian). Retrieved eight February 2021.

- ^ Castiglioni, Luigi; Mariotti, Scevola (2007). Vocabolario della lingua latina : IL : latino-italiano, italiano-latino / Luigi Castiglioni, Scevola Mariotti ; redatto con la collaborazione di Arturo Brambilla e Gaspare Campagna (in Italian) (4th ed.). Loescher. p. 1505. ISBN978-8820166601.

- ^ "Vesuvio o Vesevius nell'Enciclopedia Treccani". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Woods, Andrew W. (2013). "Sustained explosive activity: volcanic eruption columns and hawaiian fountains". In Fagents, Sarah A.; Gregg, Tracy G. P.; Lopes, Rosaly K. C. (eds.). Modeling Volcanic Processes: The Physics and Mathematics of Volcanism. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. p. 158. ISBN978-0521895439.

- ^ a b C. Plinii Caecilii Secundi. "Liber Sextus; 16 & 20". Epistularum. The Latin Library.

- ^ a b McGuire, Pecker (16 October 2003). "In the shadow of the volcano". The Guardian . Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ CIL x.i, 3806.[ total commendation needed ]

- ^ Waldstein & Shoobridge 1908, p. 97

- ^ Kozák, Jan; Cermák, Vladimir (2010). "Vesuvius-Somma Volcano, Bay of Naples, Italy". The Illustrated History of Natural Disasters. Springer. pp. 45–54. doi:x.1007/978-90-481-3325-3_3. ISBN978-90-481-3325-3.

- ^ Book 4, Chapter 21.[ full citation needed ]

- ^ Waldstein & Shoobridge 1908, p. 108 re Epigram IV line 44.

- ^ a b Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (2010) [1879]. "Vesuvius". A Latin Dictionary. Medford, MA: The Perseus Project, Tufts University.

- ^ Phillips, John (1869). Vesuvius. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 7–ix.

- ^ Charnock, Richard Stephen (1859). Local etymology, a derivative lexicon of geographical names. London: Houlston and Wright. p. 289.

- ^ Pokorny, Julius (1998–2003) [1959]. "eus, awes". In Lubotsky, A.; Starostin, G. (eds.). Indogermanisches etymologisches Woerterbuch (in German). Leiden: Leiden University.

- ^ a b c d "Summary of the eruptive history of Mt. Vesuvius". Osservatorio Vesuviano, Italian National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology. Archived from the original on 3 December 2006. Retrieved viii December 2006.

- ^ "Geology and Vulcanology | Vesuvius National Park". Parco Nazionale del Vesuvio . Retrieved 27 Apr 2021.

- ^ "Vesuvius, Italy". Volcano World. Archived from the original on five July 2008.

- ^ a b "The world'due south top volcanoes". Scenta. Archived from the original on 26 August 2010.

- ^ a b "The Pomici Di Base Eruption". Osservatorio Vesuviano, Italian National Establish of Geophysics and Volcanology. Archived from the original on 22 October 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ^ a b c "Vesuvius". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ^ "Definition of somma volcano". Volcano Live . Retrieved xi December 2006.

- ^ "Vesuvius". volcanotrek.com . Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ Stoppa, Francesco; Principe, Claudia; Schiazza, Mariangela; Liu, Yu; Giosa, Paola; Crocetti, Sergio (15 March 2017). "Magma evolution inside the 1631 Vesuvius magma chamber and eruption triggering". Open Geosciences. 9 (1): 24–52. Bibcode:2017OGeo....ix....3S. doi:10.1515/geo-2017-0003. ISSN 2391-5447.

- ^ Pliny the Younger (1909). "half dozen.16". In Eliot, Charles W. (ed.). Vol. 9, Part iv: Letters. The Harvard Classics. New York: Bartleby. [ verification needed ]

- ^ Venzke, E., ed. (ten December 2020). "What volcanoes have had the longest eruptions?". Global Volcanism Programme — Volcanoes of the World (Version 4.ix.2). Smithsonian Institution. doi:10.5479/si.GVP.VOTW4-2013. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ Invitee et al. 2003, p. 45

- ^ Invitee et al. 2003, p. 47

- ^ Livadie, Claude Albore. "An ancient Statuary Historic period village (3500 bp) destroyed past the pumice eruption in Avellino (Nola-Campania)". Meridie. Archived from the original on eighteen June 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ^ Ellen Goldbaum (half dozen March 2006). "Vesuvius' Side by side Eruption May Put Metro Naples at Risk". University at Buffalo News Center. State Academy of New York. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ^ "Pomici di Avellino eruption". Osservatorio Vesuviano, Italian National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology. Archived from the original on 18 September 2010. Retrieved viii December 2006.

- ^ Stothers, R.B.; Klenk, Hans-Peter (2002). "The case for an eruption of Vesuvius in 217 BC (abstract)". Aboriginal Hist. Bull. 16: 182–185.

- ^ Punica Viii 653–655 "Aetnaeos quoque contorquens due east cautibus ignes / Vesvius intonuit, scopulisque in nubila iactis / Phlegraeus tetigit trepidantia sidera vertex." ["Also Vesuvius thundered, throwing Etna-like fires from its crags, and its flaming summit, throwing rocks into the clouds, touched the trembling stars"]

- ^ de Boer; Jelle Zeilinga & Sanders; Donald Theodore (2002). Volcanoes in Human History. Princeton University Press. ISBN978-0-691-05081-2.

- ^ Pliny the Elder. The Natural History. Translated by John Bostock & Henry Thomas Riley.

- ^ Strabo. "Book V Affiliate iv". Geography.

- ^ Marcus Vitruvius Pollio. "Book II". de Architectura.

- ^ "Somma-Vesuvius". Department of Physics, University of Rome. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved eight December 2006.

- ^ a b Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew (15 October 2010). "Pompeii: Portents of Disaster". BBC History . Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Lapatin, Kenneth; Kozlovski, Alina (23 Baronial 2019). "When Did Vesuvius Erupt? The Evidence for and against August 24". The Iris. Getty Museum.

- ^ "Pompeii: Vesuvius eruption may take been later than thought". BBC. 16 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Scientific discipline: Man of Pompeii". Fourth dimension. xv Oct 1956. Archived from the original on 14 December 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Martini, Kirk (September 1998). "2: Identifying Potential Damage Events". Patterns of Reconstruction at Pompeii. Pompeii Forum Project, Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities (IATH), University of Virginia.

- ^ a b Jones, Rick (2004–2010). "Visiting Pompeii – AD 79 – Vesuvius explodes". Electric current Archeology. London: Current Publishing. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ Sigurdsson 2002, p. 35, on Seneca the Younger, Natural Questions, 6.ane, 6.27.

- ^ Sigurdsson 2002

- ^ Sigurdsson & Carey 2002, pp. 42–43

- ^ Zanella et al. 2007, p. 5

- ^ Zanella et al. 2007, p. 3

- ^ Zanella et al. 2007, p. 12

- ^ Zanella et al. 2007, p. thirteen

- ^ Zanella et al. 2007, p. xiv

- ^ Pliny the Younger (2001) [1909–14]. "LXV. To Tacitus". In Charles West. Eliot (ed.). Vol. IX, Part iv: Letters. The Harvard Classics. New York: Bartelby.

- ^ Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (Pliny the Younger) (September 2001). LETTERS OF PLINY. Letters of Pliny. Project Gutenberg. p. LXV. Retrieved 3 Oct 2016.

- ^ Pliny the Younger (2001) [1909–14]. "LXVI. To Cornelius Tacitus". In Charles W. Eliot (ed.). Vol. 9, Office 4: Letters. The Harvard Classics. New York: Bartelby.

- ^ Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (Pliny the Younger) (September 2001). LETTERS OF PLINY. Messages of Pliny. Project Gutenberg. p. LXVI. Retrieved iii October 2016.

- ^ "Pliny Letter 6.16". Archived from the original on eleven May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Fisher, Richard V.; et al. (and volunteers). "Derivation of the name "Plinian"". The Volcano Information Center. University of California at Santa Barbara, Department of Geological Sciences. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ Janick, Jules (2002). "Lecture nineteen: Greek, Carthaginian and Roman Agronomical Writers". History of Horticulture. Purdue University. Archived from the original on xviii July 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ Josephus, Flavius. "twenty.vii.2". Jewish Antiquities. Also known to take been mentioned in a section now lost.

- ^ a b Giacomelli, Lisetta; Perrotta, Annamaria; Scandone, Roberto; Scarpati, Claudio (September 2003). "The eruption of Vesuvius of 79 AD and its impact on human environment in Pompei". Episodes. 26 (three): 235–238. doi:x.18814/epiiugs/2003/v26i3/014.

- ^ "Pompeii, Stories from an eruption: Herculaneum". Soprintendenza archeologica di Pompei. Chicago: The Field Museum of Natural History. 2007. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Vesuvius Causes Terror; Loud Detonations and Frequent Earthquakes, The New York Times, six April 1906

- ^ Vesuvius Threatens Destruction Of Towns; Bosco Trecase Abased, The New York Times, 7 April 1906

- ^ Scandone, Roberto; Giacomelli, Lisetta; Gasparini, Paolo (1993). "Mount Vesuvius: 2000 years of volcanological observations" (PDF). Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 58 (1): 5–25. Bibcode:1993JVGR...58....5S. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(93)90099-D.

- ^ Stevens, Robert (1944). Mt Vesuvius erupts nigh Naples, Italy in 1944 (The Travel Film Archive). Naples: Castle Films, YouTube. Archived from the original on 30 Oct 2021.

- ^ Giacomelli, L.; Scandone, R. (1996–2009). "The eruption of vesuvius of March 1944". Esplora i Vulcani Italiani. Dipartimento di Fisica E. Amaldi, Università Roma Tre. Archived from the original on thirty Dec 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ Kaiser, Don. "The Mount Vesuvius Eruption of March 1944". Archived from the original on iii November 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- ^ "Melvin C. Shaffer Globe War Ii Photographs". Key University Library (CUL), Southern Methodist University (SMU).

- ^ a b Kilburn, Chris & McGuire, Pecker (2001). Italian Volcanoes. Terra Publishing. ISBN978-ane-903544-04-four.

- ^ Giacomelli, L.; Scandone, R. (1996–2009). "Activity of Vesuvio between 1631 and 1799". Esplora i Vulcani Italiani. Dipartimento di Fisica E. Amaldi, Università Roma Tre. Archived from the original on nineteen January 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Hale, Ellen (21 October 2003). "Italians trying to prevent a mod Pompeii". USA Today. Gannett Co. Inc. Retrieved eight May 2010.

- ^ Arie, Sophie (v June 2003). "Italia ready to pay to clear slopes of volcano". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Gasparini, Paolo; Barberi, Franco; Belli, Attilio (16–18 October 2003). Early Warning of Volcanic eruptions and Earthquakes in the Neapolitan expanse, Campania Region, South Italia (Submitted Abstract) (PDF). 2nd International Conference on Early Alert (EWCII). Bonn, Germany. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2009. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ "Vesuvius". Naples: Osservatorio Vesuviano, Italian National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ "The National Park". Vesuvioinrete.it. 2001–2010. Retrieved seven May 2010.

- ^ Smith, Paul (March 1998). "Thomas Cook & Son's Vesuvius Railway" (PDF). Nippon Railway & Transport Review.

Bibliography

- Guest, John; Cole, Paul; Duncan, Angus; Chester, David (2003). "Chapter two: Vesuvius". Volcanoes of Southern Italian republic. London: The Geological Gild. pp. 25–62.

- Sigurdsson, Haraldur (2002). "Mount Vesuvius before the Disaster". In Jashemski, Wilhelmina Mary Feemster; Meyer, Frederick Gustav (eds.). The natural history of Pompeii. Cambridge Britain: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. pp. 29–36.

- Sigurdsson, Haraldur; Carey, Steven (2002). "The Eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79". In Jashemski, Wilhelmina Mary Feemster; Meyer, Frederick Gustav (eds.). The natural history of Pompeii. Cambridge Uk: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. pp. 37–64.

- Waldstein, Charles; Shoobridge, Leonard Knollys Haywood (1908). Herculaneum, by, present & futurity. London: Macmillan and Co.

- Zanella, E.; Gurioli, L.; Pareschi, M.T.; Lanza, R. (2007). "Influences of urban material on pyroclastic density currents at Pompeii (Italia): Office II: temperature of the deposits and take a chance implications" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 112 (B5): B05214. Bibcode:2007JGRB..112.5214Z. doi:x.1029/2006jb004775.

External links

- Purcell, N.; Talbert; Elliott; Gillies (20 March 2015). "Places: 433189 (Vesuvius Thousand.)". Pleiades. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Fraser, Christian (10 January 2007). "Vesuvius escape plan 'bereft'". BBC News. Naples: BBC. Retrieved eleven May 2010.

- Garrett, Roger A.; Klenk, Hans-Peter (Apr 2005). "Vesuvius' adjacent eruption". Geotimes. Archived from the original on 12 May 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- "Vesuvius: The making of a catastrophe: Il problema ignorato". Global Volcanic and Environmental Systems Simulation (GVES). 1996–2003.

- Smithsonian Institution's Global Volcanism Program (GVP) (entry for Aira / Sakurajima)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Vesuvius

0 Response to "Story of How Mt Vesuvius Will Erupt Again to Reach the Woman in the Water"

Post a Comment